It is difficult to overestimate the tremendous value of editors. The contributions that authors make to their respective fields, and their impact on the readers that encounter their work, can’t be overstated either, of course—but it is equally important to remember that no truly great author goes it alone; there are always strong editors behind the scenes, shaping the individual stories themselves as well as the publishing world at large. The Hugo Awards are named for an editor, after all.

Yet I can count most of the editors I recognize by name on one hand. Even with such a limited group to choose from, only two have had an extremely significant, identifiable impact on me as a reader: Terri Windling and Ellen Datlow. I could never hope to cover everything the two have contributed to the publishing world—their careers have stretched too far and are too varied and far-reaching for me to do them full justice. However, there are several projects that are worth looking at in order to appreciate their impact and get a sense of how influential their work has been, and continues to be.

Windling* and Datlow have had an editorial partnership spanning over three decades, and their names, for me at least, have stood as markers of quality for much of my reading life. From the time I first discovered their Year’s Best anthologies, I have looked to them as arbiters of the very best in genre storytelling. Now, it’s quite possible that I’m making a gross generalization based on my own limited experience (it’s been known to happen) but, despite winning several prestigious awards, Datlow and Windling are quite possibly two of the most recognizable editorial names in modern fantasy and horror, and yet I see little aside from a few occasional interviews that give them the credit they deserve. Jeff and Ann VanderMeer might be giving them a run for their money in the coming years for the title of Most Famous Editing Pair in Speculative Fiction, but Datlow and Windling have a significant head start on their side.

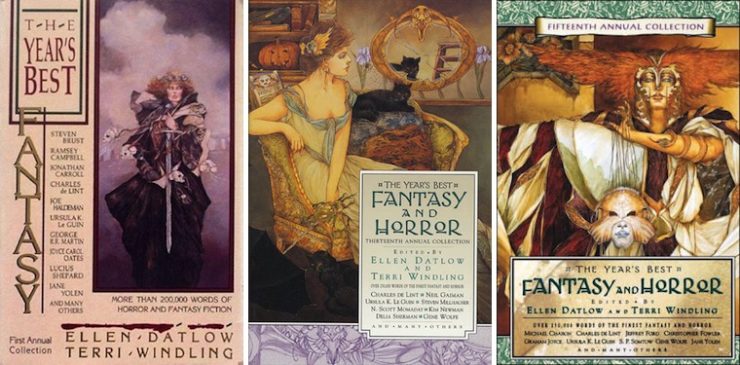

Datlow and Windling are perhaps best known as the editing team behind The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror anthologies published from 1987 to 2003 (Windling left the project in 2003; Datlow continued through 2008). These anthologies were amazing not just because they provided a stellar collection of stories that highlighted each year’s most talented writers, but because they also expanded the boundaries of the fantasy and horror genres to encompass more than the traditional forms readers had come to expect. They often included magical realism, urban fantasy, weird fiction, and many other subgenres that were either just emerging or dismissed as too “literary” at the time.

It’s also vital to note that for readers, these anthologies were more than just collections of (really excellent) short fiction: they were also compendiums of knowledge encompassing all things fantasy and horror, from films and comics to television and magazines. The beginning of each volume, often stretching over a hundred pages or more, offers a roadmap to the major publishing and media events of the year, including incisive commentary that demonstrates just how fully immersed these two editors are in their genres of choice. As someone who discovered fantasy through the library rather than through other a community of other readers (and without regular recourse to the internet until much later), these summations gave me a sense of what was happening in the larger world of genre fiction—something that had always felt rather static and abstract until I was able to see how much happens in just a year, in a larger context.

One reviewer of the 13th Edition summed it up rather succinctly: “you can’t page through this volume without realizing how vibrant this field really is.” Recently, I’ve gone back through that same edition (published in 1999) and learned things I can’t believe I missed before. For instance, how on Earth did I not know that the English-language script adaptation of Princess Mononoke, one of my favorite movies of all time and my own personal gateway anime, was written by none other than Neil Gaiman?! This particular edition came out the year I would have seen the movie, and paging back through that volume now feels like opening a time capsule into my earliest days as a budding genre fan.

In terms of their partnership, each editor has a specialty—Ellen Datlow focuses more on horror while Terri Windling’s wheelhouse is fantasy—yet rather than simply taking a divide-and-conquer approach, their work illuminates and explores the relationship between fantasy and horror. Fantasy and science fiction are so often and automatically lumped together that it can be easy to overlook how much DNA fantasy and horror really share…something that becomes even clearer when you look at another anthology series the two produced, beginning with Snow White, Blood Red in 1993.

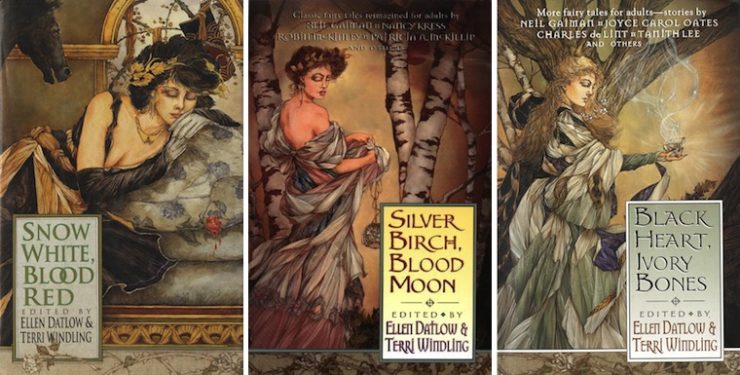

Anyone with even a passing interest in fairy tales knows that many of the versions we encounter today have been sanitized over the years and rebranded as children’s stories. Disney has become the most famous bowdlerizer of fairy tales, but the genre in general has been steadily transformed since the 19th century—something Terri Windling highlights at the start of her introduction to Snow White, Blood Red. In that intro, she makes clear that the intent of the collection (and eventual series) she and Datlow had undertaken is not to simply update old stories with modern flourishes but to recapture the original darkness of fairy tales, bringing them back to the adult audience that has forgotten their once-considerable power. As with the Year’s Best anthologies, Datlow and Windling focus on their respective areas of genre expertise. Unlike those broader anthologies, however, the fairy tale collections don’t ever feel like the two separate genres are sitting side-by-side, but are united in one vision, despite the deliberate split in the title (a convention that carries through the rest of the series).

It is through these collections that I first discovered the pleasures of stories based on well-known tales told through new, startling perspectives, and found that retelling older stories has a special kind of magic when done well. These books are also where I first discovered Tanith Lee and Jane Yolen, two writers whose work has long been a part of my own personal canon in fantasy. Each of the seven volumes they eventually produced together—ending with Black Heart, Ivory Bones in 2000—contains some of the most compelling (and often disturbing) versions of fairy tales I have ever encountered and nearly all of them hold up beautifully.

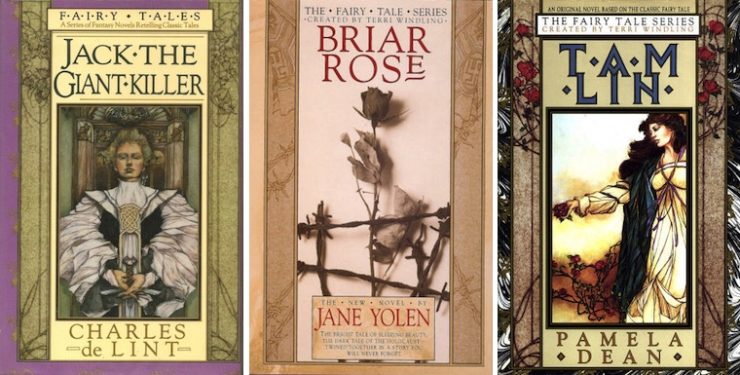

Speaking of retellings that hold up remarkably well, Terri Windling is also the editor of the “Fairy Tale” series, a handful of novels written by authors like Patricia C. Wrede and Charles de Lint that were published in the late 80s and early 90s. While this series was done without Ellen Datlow’s direct participation, I still find that I tend to mentally link it to their partnership. The fairy tale theme is, of course, the most obvious connection, but the novels also share an aesthetic link with their co-edited work thanks to the illustrator and designer Thomas Canty, who designed the covers for both the novel series and the fairy tale anthologies in his distinctive Pre-Raphaelite-inspired style. (Canty was also the designer and illustrator for the Year’s Best anthologies; it could be argued that much of the work I’ve mentioned so far might be considered a three-way collaboration in some ways). Despite the eternal injunction to never judge a book by its cover, I must confess that I probably discovered Windling and Datlow (and through them, many, many excellent writers) thanks to Canty’s artwork, which was less afraid to be overtly feminine than a lot of the more traditional fantasy artwork at the time, even if his style eventually became a bit overused.

I’ve yet to read every novel in the series, but definitely worth noting are Jane Yolen’s Briar Rose, which tells the story of Sleeping Beauty through the lens of the Holocaust, and Pamela Dean’s Tam Lin, based on the Celtic ballad of the same name (and a book that makes college life seem impossibly romantic). Whether these stories would have come into the world without Windling as editor is debatable given the talent of the writers, yet I am inclined to believe that her passion for the subject—and her ability to champion the most interesting versions of familiar stories—is at least partially responsible for their existence.

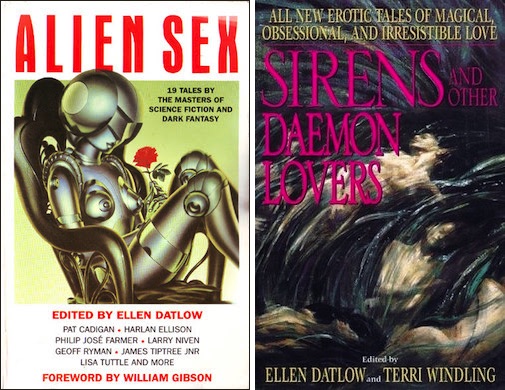

Ellen Datlow has also done quite a bit of solo work, but as I’m not personally much of a horror fan in general, the most notable anthology in my personal experience (outside of the Best Horror of the Year anthologies she currently edits) is the Alien Sex anthology, a science fiction collection published in 1990. I mean, how do you resist a title like that? I certainly couldn’t, and immediately bought it when I ran across an old paperback copy in a used bookstore a couple of years back. Though very different from fairy tales on the surface, the stories in Alien Sex prove that Datlow, like Windling, has always been interested in stories that do more than entertain, stories that dig deep into the human psyche and the more primal elements of our natures. In 1998, Datlow and Windling would revisit the murky waters of love and sex via the realm of myth and legend in their anthology Sirens and Other Daemon Lovers, a stellar collection of erotic fantasy that continues the boundary-stretching tradition of their partnership.

In an interview with Locus Magazine in June of 2016, Windling and Datlow discuss what makes their partnership work so well. Like any good creative and/or business arrangement, they know how to divide their tasks according to their strengths (and not just along genre lines). Windling, for example, writes many of their introductions and is frequently in charge of the table of contents (a task that takes more finesse than you might expect) while Datlow is often the one to deal directly with writers and take charge of organizational issues, prompting Windling to remark that Datlow “makes the trains run on time.” The fact that their joint projects feel so seamlessly put together is a testament to how well they make this arrangement work. Just like editing a story is more than polishing grammar and syntax, assembling an anthology is so much more than simply compiling a few good stories.

In that same interview, the two discuss their process of choosing stories for various collections, sharing how, after combing through hundreds of possibilities, each potential choice much stand up to another half-a-dozen rereads before it can be accepted. Windling also outlines how the stories are arranged, a meticulous process with each story placed in the perfect orientation with the others to allow them to inform, echo, and bounce off each other. Operating on a level beyond a simple assemblage of stories, the anthologies Datlow and Windling create are treated like an artform all their own.

I’ve spent a lot of time discussing these two influential editors without mentioning what is, to me, one of the most salient points to consider: they are both women. The fantasy and horror genres, like science fiction, are still considered to be largely male-dominated fields. Windling and Datlow have been collaborating and collecting together for over 30 years in these genres that are, despite many gains, still struggling to figure out how to redress the issues of sexism and exclusion that have plagued them from the very beginning. Windling and Datlow’s ability to make names for themselves in such a world—to be considered expert enough to compile collections that are a measuring stick of their respective genres—is certainly part of what makes their contributions significant. The other part is simply that they are damn good at what they do.

Like any good editor, Windling and Datlow rarely call attention to themselves. The introductions to their work are often about the broader cultural inspirations behind their choices and why the projects spark their particular interest, with a distinct focus on the writers and their contributions. Yet, as I sit here writing this, surrounded by over a dozen volumes emblazoned with their names (representing merely a fraction of their overall output), I can’t help but feel that Datlow and Windling’s efforts have made an undeniably wonderful, powerful impression on their corner of the publishing world. Their projects have expanded their respective genres to include a range of stories that may have languished outside of the prescribed boundaries of fantasy and horror; meanwhile they could also be credited with reintroducing the power of fairy tales to a whole new audience.

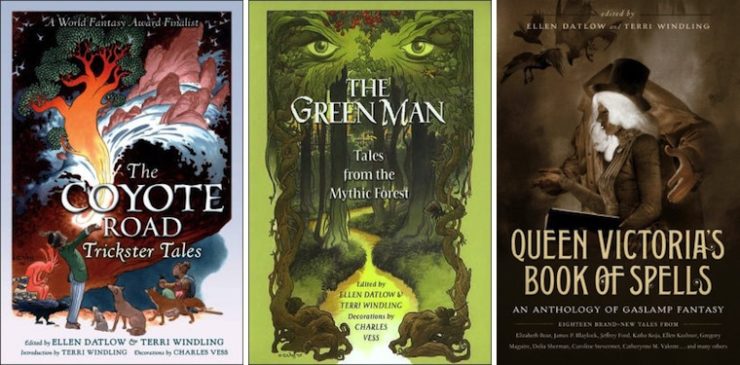

More recently, it seems that Datlow and Windling have turned their attention to subgenres and themed anthologies, from The Coyote Road (trickster stories) and The Green Man (forest tales) to Teeth (vampires) and After (post-apocalyptic stories). My own most recent acquisition, Queen Victoria’s Book of Spells, is a collection of gaslamp fantasy published in 2013 that, much like their other work, feels ahead of its time as it plumbs the darker depths of a subgenre that has too often been consigned to the realm of lighthearted romps and children’s stories.

With such a massive catalog of volumes produced both together and apart, I may spend the rest of my life trying to catch up and read all of the stories Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling keep collecting and compiling so brilliantly—and as a devoted reader of their work, I couldn’t be happier about that prospect.

*It’s well worth noting that Terri Windling is a successful author, essayist, and artist as well as an editor, but that’s a conversation for another time!

Amber Troska is a freelance writer and editor. When she isn’t reading, you can find her re-watching Stranger Things again.